2021 Fall Book notes: Called to love

2021 Fall Book notes: Called to love

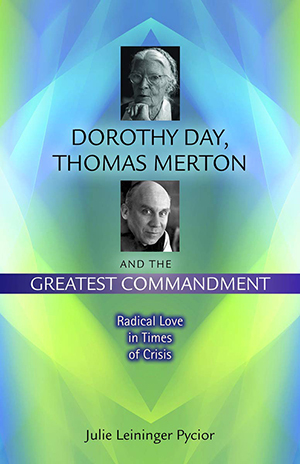

In Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton and The Greatest Commandment (Paulist, 2020), Julie Leininger Pycior recounts the story of two improbable friends who, while worlds apart, supported and encouraged each other in their respective vocations. The monk/hermit separated from the world, and the laywoman in the middle of the hustle and bustle of a house of hospitality had much more in common than is visible at first glance. Unlike most friends, Day and Merton  never met, but like most friends, they had their ups and downs, including a misunderstanding that threatened to end their friendship for good. But ultimately, what brought the two together was their vocation to love, even as they each lived out this vocation in different ways.

never met, but like most friends, they had their ups and downs, including a misunderstanding that threatened to end their friendship for good. But ultimately, what brought the two together was their vocation to love, even as they each lived out this vocation in different ways.

In Matthew 22, Jesus gives us the greatest commandment, to love God above everything, and to love our neighbor as ourselves. Jesus calls each of us to Love; how we are to love is how we live out that vocation. In 1959, a year after his famous epiphany at the corner of 4th and Walnut Street, which made him understand more profoundly how God was calling him to love all, Merton began corresponding with Day. For her part, Day had felt the call to love her neighbor decades earlier. She prayed that “some way would open up for me to use what talents I possessed for my fellow workers, for the poor.” And so, it was that a short while later, she and her friend, Peter Maurin, began both the Catholic Worker newspaper and houses of hospitality. As explored by Pycior, it was thus that “from seemingly opposite perches, the contemplative and the movement leader began encouraging each other in their lonely call: contemplation and action in the service of love of God and love of neighbor.”

Their friendship could not have come at a better time, for the 1960s proved to be a turbulent time for both. As Pycior describes, “Day and Merton were forging a shared prophetic witness of contemplation combined with radical witness, as they confided in each other their hopes and fears.” For Merton this meant becoming a hermit while writing about peace in some of the most influential publications, including Day’s own Catholic Worker newspaper. For Day this meant becoming one of the foremost anti-war social justice activists in the Catholic Church. This combination of prophetic witness of contemplation and radical witness often landed them in hot water with members of the church hierarchy.

As Merton wrote more about current affairs and explored eastern traditions, many thought that he was going to quit his vocation as a monk. Some of his friends even encouraged him to leave the monastery. But not Day, who understood the importance of his vocation, just as she had a vocation that others found hard to understand. She encouraged his anti-nuclear writings as a gift from God and always requested his prayers for herself and her community. Pycior writes that to Day, “more important than any timely tips was the sure knowledge that her Trappist correspondent was praying for her intentions, as were the novices under his charge.” As a widely respected and admired Catholic priest and writer, Merton’s writings and endorsement of the peace movement were consequential.

For her part, Day’s vocation to love was to be lived out in giving witness to social justice issues by her activism and journalism rooted in a life of poverty and deep prayer. In the middle of the sometimes chaotic reality of the house of hospitality, Day had a deep spiritual life that gave her the strength to do all she set herself out to do. With her radical witness, living in poverty among the poor, she inspired many to join her work or advocate for the poor in other ways. As Pycior writes, “her radical witness to love of God and neighbor inspired elite figures such as Wilbur H. ‘Ping’ Ferry and Sargent Shriver to redouble their own efforts to help build a society in which it would be easier for people to be good.”

The contrast between their vocations is most evident when both were advocating for the Second Vatican Council to promote nonviolence and peace and condemn nuclear warfare. Merton, trying to reach the Council fathers, wrote a piece invoking the 6th century Saint Maximus, who wrote that if we lack peace, it is because we privilege our desires and most importantly that we should have at the center of our hearts the greatest commandment: to love one another. In a separate piece, Merton openly challenged the stance of American prelates, reminding them that they were called to obey the gospel of love and calling the conflict in Vietnam senseless warfare. Day went to Rome and fasted and kept vigil before the Blessed Sacrament during the 11 days that the Council fathers were deliberating on the issues of peace and nonviolence. In the end, the Council condemned nuclear warfare, much to the jubilation of both Day and Merton.

But while they supported and encouraged each other in their respective vocations and call to radical witness, as with any friendship, Day and Merton had their disagreements. First, Merton believed that force was justified in certain circumstances, while Day believed it was never justified. Second, Pycior notes that in 1964 Merton hosted a retreat entitled “The Spiritual Roots of Protest” to which only men were invited, and this was the only year during the 1960s that she and Merton did not correspond.

Lastly, their greatest disagreement came when Catholic Worker Roger LaPorte burned himself alive in protest against the Vietnam War. Merton was quick to condemn the action and hold the Catholic Worker Movement responsible. This hurt Day tremendously, who was grieving LaPorte’s death and his actions. But, in her love for LaPorte, whose suicide threatened the reputation of the Catholic Worker, as Pyocir notes, Day preferred to focus on the greatest commandment: “All of us around the Catholic Worker know that Roger’s intent was to love God and to love his brother.”

In the end their friendship survived. As Pycior notes, “Indeed, this episode reveals that when tensions arise between colleagues in a time of great national crisis, those tensions do not have the last word for those who strive to root themselves in the great commandment of love.” They both continued to support each other’s vocations and pray for each other, each understanding the importance of the other’s vocation. Although their vocations were different, what mattered was the Greatest Commandment and how they gave radical witness to it. Today Pycior’s book is a timely reminder that as Christians we are called to give radical witness to love of neighbor from the different vocations God has called us to.

Sister Graciela Colon, S.C.C., is a member of the Sisters of Christian Charity based in Mendham, N.J. She ministers as the supervising attorney in the Immigration Legal Services Department at Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of New York. Colon also serves on her congregation’s Justice, Peace, and Integrity of Creation team. She holds a juris doctor from The Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law and a bachelor’s degree in Political Science from Fordham University.

Published on: 2021-11-02

Edition: 2021 HORIZON No. 4 Fall, Volume 46

CONNECT WITH NRVC

via Zoom

Chicago, IL

Chicago, IL

© 2026 National Religious Vocation Conference NRVC

( * ) Site design and programming by ideaPort, LLC

Leave a comment

This article has no comments or are under review. Be the first to leave a comment.

Please Log-in to comment this article